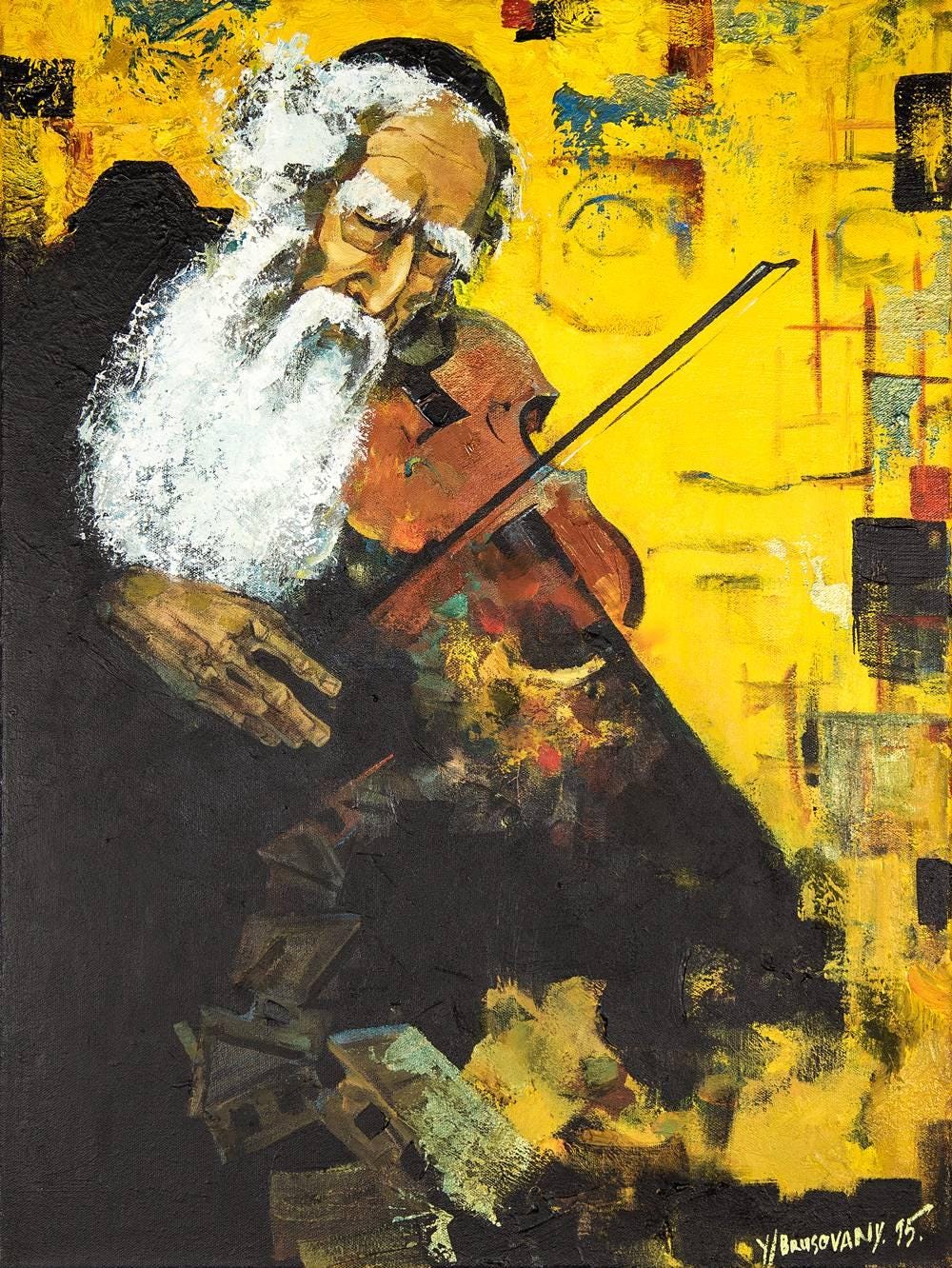

holy elder beard music

is this a fairy tale... i'm pretty sure it's not

Hashem won’t end our exile if the music isn’t right. That was the consensus in the village. Can’t you hear it rabbi, the G is completely flat, Then tune it properly, But I can’t, look see. He turned the peg on the fiddle just the tiniest bit, and then the G was sharp. Then back down again to flat. It goes on like this, with every string of every violin in the village and beyond... and if the instrument is not in tune, then nothing will sound right… it’s as you say rabbi… us jews, no one knows how to suffer like us… we have made an art of it… and nowhere is that art more alive than in the cry of a shrieking fiddle… that’s where the soul of our people lives, that is the voice that speaks to Hashem, and if it’s not right he won’t end our exile.

Maybe you should be the teacher... That was rabbi Katz’ thought, now rarely expressed, to the town’s violinist’s repeated complaints. When, and lately if, the rabbi expressed the reasonable objection that, according to the same legend, during all the millennia of playing the music right they remained in exile, and then explained that by all laws of logic that fact leads to one of two perhaps mutually exclusive but independently indisputable conclusions, that either Hashem doesn’t care about the music, or it wasn’t played right before either, the violinist would dismiss the rabbi with something that trumped logic, The books say the music is only right with the hair from the beard of a holy elder, and now we don’t have any. So the rabbi was not inclined to go through it again. Once it was written down it was over. Like the chinese, the jews always write everything down. And like the chinese, when two elders or two sources or two stories disagree they stick to the disagreement, rather than try to find a solution or a synthesis. Those were words, and therefore concepts, perhaps appropriate for latins and greeks, respectively, but the jews seek after signs, as Saul says, he may be a traitor but by Hashem he writes with the eloquence of a thousand jews… and by then the rabbi was lost in thought, contemplating the nature of jewry, often a rabbi’s favorite topic.

It’s tough being the spiritual leader of people who will believe anything. And rabbi Katz was getting too old for these shenanigans. His flock was convinced that the fiddles just didn’t sound right now that rabbi Nachner was dead. No one knew how old he was when he died, but according to popular sentiments, the music had started to die long before that. Rabbi Katz didn’t know the origin of the legend. When he was born the old wise man was already regarded as a saint. The hairs from elder Nachner’s beard were holy, and when used to string a fiddle, the instrument spoke directly to the heavens. The backstory involved every age having its own holy rabbi of untold years providing beard hairs for fiddles all the way down to the patriarchs and beyond, back to whatever time fiddles were first invented. And of course, now that it was written down, it was indisputable, simply by the fact that it had, at some point, been disputed. Why would anyone go through the trouble of writing down and copying over centuries something that was not important.

Using that same logic, rabbi Katz had tried and failed to find something in the Torah, in the Talmud, in the Mishna or the Haggadah, anywhere, any rule or ruling that would disprove or at least prohibit the charade and thus put an end to all the nonsense. But of course, even if he had found it, it wouldn’t have mattered. The madness would come out some other way, it always did. Within the same book that first endorsed the practice there were objections, but the objectors were dismissed by the common arbitrage that whoever spoke last was wrong. That of course guaranteed that some very stupid ideas would come to be regarded as holy writ.

For centuries people sought the beard of a holy elder, who lived in some village, no matter how far. And in this age, it turned out to be their village, and their own elder had supplied beard hairs to string violins far beyond its borders, so that jews that looked nothing like them, and spoke another language, used to visit often. When rabbi Katz was a boy, the legend and the elder’s beard were still in its heyday. Elder Nachner was a shrewed businessman and employed several people to obtain, sort by thickness, inspect for quality and prepare for sale his beard hairs. And more importantly he was a natural salesman, and had the most distinguished fiddlers in all of jewry become brand ambassadors for Nachner’s beard. But the years caught up to him eventually. He was too old. His acumen, his influence, not to mention the tensile strength of his beard hairs, were waning. The strings would break easily, and wouldn’t keep their tuning. And when he died, three or so years before, there was yet no true competitor. No new elder had taken Nachner’s place. And all the people could do was complain.

None of these complaints would have graduated from annoyance to trouble if human nature was different. As certainly as a B seventh wants to resolve to an E major, men and women want stories to give them hope, and if one failed or died or fell out of favor or fashion for whatever reason, they would eventually make up another one. And thus holy elder Abravanel, not the man, the legend, was born. He lived very far away from them, far enough that every bit of information, perhaps including his name, had suffered the inevitable corruption of word of mouth, in this particular instance becoming bigger and bigger, though not enough yet to make it to any book.

Yet, of course, names get added to books only after gaining fame outside of them. So that, for now, deterred no one. If someone from their village went there, they would be the jews that looked nothing like the others, and that spoke a foreign language. And it would be a very long and very perilous and very costly trip. The village would be abandoned, and everyone would be poorer than they already were, and no closer to returning to the holy land. But these practical concerns mattered nothing to the people. The number of miracles attributed to the new elder, and his beard hairs, were already in the hundreds. And it had only been a year or so. Of course, if it meant only the violinist, that would be no problem. They could live without hearing a professional playing the fiddle. Or even if it was all violinists in town, professional and amateur alike. It would still be ok. But the legend was now too big. The people too eager. And everyone in the village, the young, the old, even the infirm, wanted to make a pilgrimage to meet the holy elder, obtain his blessing and secure a reasonable supply of beard hairs, they were sure to go up in value.

The night before the pilgrimage was to begin, leaving rabbi Katz alone with the sheep and the goats for about a year, at least, as even his wife and sons wanted to go meet the holy man, he had what he later perceived to be a moment of clarity, but at the time it felt like the madness natural to close encounters with divinity. A man, dressed in dark indigo robes, with bright auburn hair and beard and hazel green eyes, appeared to him, pointed at him, and said, You. Then he woke up, and knew what to do. All night he worked at it, and then at daybreak, when the people were ready to leave, instead of the blessing he was meant to call upon them from the heavens, he played his fiddle, stringed carefully with his own wise and holy beard, and the people decided to stay.

Are you saying that only old holy dudes know how to complain properly? Because that's believable.

I'm sure the gypsies of Europe are actually the jews. The balkan jews especially, fit the beauty threshold